Huntington (2016) writes, “The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion, but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence”. Talking about the enormous Chinese naval power of the past and their official overseas expeditions compared to the behavior of their Western counterparts Kennedy writes, “The Chinese never plundered and murdered – unlike the Portuguese, Dutch, and other European invaders of the Indian Ocean”.

-(Excerpt from the article).

######################################################################

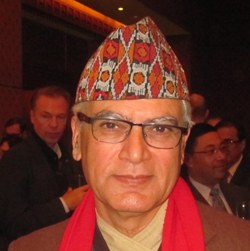

Dr. Shambhu Ram Simkhada

Former Ambassador

and Life Member of Nepal Council of World Affairs (NCWA)

Kathmandu

War is not a destiny; it is a human choice, a failure of politics, economics, diplomacy, and security policy.

International Relations (IR) is the study of great power relations and how they affect the world. Understanding and conduct of contemporary IR based on old assumptions can be as erroneous and risky as concluding the inevitability of war between two 21st Century great powers based on what a scholar reminds us of the “Thucydides’ Trap”, history of two warring Greek city-states because they could not accommodate each other’s national interests.

What is Graham Allison of Harvard’s Kennedy School, arguably one of the greatest global institutions of higher learning and powerhouses of ideas, trying to convey by characterizing 21st century America-China relations by 5th Century BC Greek city-states? Do scholars and practitioners of IR realize the irony?

History without Lessons:

Works of Chanakya, Machiavelli, Sun Tzu, Thucydides, and much more present great wisdom on statecraft, governance, art, or science of war of their times. However, how should they be understood and applied by scholarship and leadership in the digital age of artificial intelligence, killer robots, and hypersonic weapons of mass destruction capable of destroying the world many times? Reflecting on this is vital as technology has transformed human enterprise so fundamentally that old theories can neither explain nor be used to resolve most problems of today.

That may be the reason humanity keeps repeating again and again what it keeps vowing “never again. Preventing US-China competition from turning into confrontation is critical in the study and conduct of contemporary IR and its implications are profoundly significant not just for them but the whole world (Simkhada, 2021).

Rise of the United States of America:

In the march of history, the rise of the United States, on the strength of its European intellectual history but different favorable location, large size, rich natural endowment, politics of individual liberty contributing to innovative and advancing technology and attraction, co-option and assimilation of global talent and manpower is one of the most significant megatrends shaping the current world.

Its visionary founding fathers established institutions able to combine local autonomy with a central authority, and individual liberty contributing to collective prosperity and security giving the US advantage over many other great powers built around narrower fundamentals of national power. Consequently, in the post-World Wars, and even more so in the post-Cold War era, the US emerged as the unchallenged global superpower influential in all fields of human endeavor, intellectual, ideological, economic, technological, and military, like no other one country in world history.

In the book What If? some of the world’s foremost historians provide fascinating accounts of how the world would have been very different if certain events had gone differently or if certain major powerful actors had behaved differently at different periods of history. But there is no denying that as a society/country, the US is unparalleled in its ability to assimilate peoples of the world, of cultures, religions, races, and beliefs (Munroe, 2014).

This US rise is significant in many ways, most notably in its appetite for asserting the superiority of its political, economic, social, and strategic model on the “power of its liberal-democratic example” as far as possible but with the most illiberal use of its national and allied military power when Washington feels necessary. US President John F. Kennedy’s famous inaugural speech, Samuel Huntington’s argument “The West’s universalist pretensions increasingly bring it into conflict with other civilizations, most seriously with Islam and China” and the so-called Hegemonic Stability Theory of IR suggesting that the international system is more likely to be stable when a single nation-state (hegemon) remains the dominant power has come under scrutiny in many ways best articulated in the University of Chicago Professor John J. Mearsheimer in his Theory of Offensive Realism and the Rise of China as well as his many other articles and lectures abundantly substantiate this reality.

The duality in dealing with what America sees as an adversary in values (ideology and religion), interests (national and sometimes even personal), combined with national “exceptionalism” is reinforced by its all-powerful military-industrial complexes and their widespread and enduring hold on domestic political-economy, national and global security, and vision of IR.

The foundation of individual liberty combined with a passion for “winning” and open to use force for it in today’s world of technologically empowered individuals and nation-states makes the US a society and global superpower of contrasts. One America is liberal-progressive, tolerant, open, generous, dynamic, united, inspiring, resilient, globalist, and confident. Is there any other better example of the integration of people of all races, religions, cultures, and backgrounds from anywhere in the world into the fabric of its society than the US? This America is sometimes shadowed by the impression of the other looking fundamentalist, selfish, divided, divisive, vindictive, violent, isolationist, suspicious, and belligerent.

Such internal paradoxes, (socio-economic disparity, gun violence, drug addiction, treatment of minorities (Black lives matter), extreme internal political polarization, global policeman’s role, and never-ending wars create serious political stress and economic distress for itself and others.

Social media and TV networks, often beaming only bad news as new in front of global audiences make the US call for a united front against authoritarianism and in defense of democracy, HR, rule of law less convincing, unlike the cheers it used to receive when evoking those messages in the past. As if echoing that, President Biden pointed out in his latest State of the Union Address, “Our strength is not just the example of our power, but the power of our example. Let’s remember the world is watching”.

The duality in Western political thought and behavior is not new. The Magna-Carta evolved to guide British politics as the birthplace of Parliamentary (Westminster) Democracy but would not apply to the Colonies. Liberté, égalité, and fraternité, the founding principles of the French Revolution, would not apply to the Colonies, and Life, Liberty, and Pursuit of Happiness were not meant for the blacks in the US for a long time. Christian values of kindness, honesty, and charity were important in shaping Western social and political order, but Samuel P.

Huntington and Paul Kennedy are quite candid that Western power and not culture or values were the instruments of their global power projection.

Huntington (2016) writes, “The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion, but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence”. Talking about the enormous Chinese naval power of the past and their official overseas expeditions compared to the behavior of their Western counterparts Kennedy writes, “The Chinese never plundered and murdered – unlike the Portuguese, Dutch, and other European invaders of the Indian Ocean”. This difference in domestic political values and their application towards what the West saw as the “Other”, always existed in the West. The anti-globalist ultra-nationalism and populism best represented by the Donald Trump Presidency and the Capitol insurrection glaringly exposed the dangers of this duality to the West itself and also to the rest of the world.

Rise of China:

Modern China’s socio-economic transformation under the firm guidance of the Communist Party (CPC), now celebrating 100 years of its founding, has been the other most spectacular and consequential mega trend with intellectual, ideological, economic, and strategic implications not just for China but the whole world. China’s rise is particularly significant because some Western scholars were calling the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe and the fall of the former Soviet Union End of History (Fukuyama, 1992). As this debate was going on elsewhere Mao’s Communist China was transforming with Deng’s “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” leading to where China is today, poised to be the largest economy of the world and determined to reject any external hegemony by Xi Jinping’s Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nations. With a display of its spectacular economic rise and military modernization, both the posture and speech of the General Secretary of the CPC and President of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Xi Jinping during the recent centenary celebrations of the CPC and projections for the centenary of the PRC signal China’s rise so far and ambitions for the future, primarily the targets for the centenary of the PRC in 2049.

Shaking Intellectual Pedestal:

Globally, tremendous developments in information technology have skyrocketed popular demands for a more equitable sharing of political power and economic benefits within and across societies. But the winners take all mindsets at the top making the management of politics and economics more complex everywhere, leading to the current crisis in the global political economy. But new ideas to bridge the governance deficit are in short supply, with growing uncertainties of how the mid-21st Century world manages the internal political economy, long-festering energy, environment, food, and finance (2E2F crisis), now manifest in the serious Climate, Covid, and Conflicts (3 Cs crises) profoundly affecting global society and IR.

Amidst such crises, talking of the intellectual dilemmas facing the world today, in the Foreword of the book Commonwealth by Jeffery Sachs, Edward O. Wilson, writes “We (mankind) exist in a bizarre combination of stone age emotions, medieval beliefs (and institutions) but Godlike technology. This is how we have lurched into (what we call) the 21st Century” (Sachs, 2008). If this is how thinkers in societies regarded as most advanced, from which, one way or the other, all are impressed and influenced, think, and write, one can imagine the state of societies at the tail end of the spectrum of intellect content in what an Indian scholar-diplomat calls “the tragedy of mimicry”.

In this global paradigm flux, the Chinese model of the State fulfilling the needs of party and state elite for a decent living but severe punishment for corruption and anti-party/state activities may not be so different from the meritocracy Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore adopted to transform itself from the Third to the First World. If the CPC rule can fulfill the growing needs of the Chinese people and avoid a major internal turmoil and external crisis China’s rise could continue.

In that case, the global Democracy debate may bring not just the Chinese experiment of successful socio-economic transformation under the strict political control of the CPC but also the shaking intellectual pedestal on which monuments of peaceful and prosperous democracies are built and sustained elsewhere also into the spotlight. Not least because China is moving away from a rural, agricultural society and the world’s factory producing low-cost consumer goods to a high-tech and advanced knowledge economy.

As some of China’s earlier partners in progress come under pressure of “decoupling” making China their biggest technological-economic competitor and ideological-security threat, all sides in the global ideological divide may face the challenge of innovation not just in technology and economics but also in the management of political-economies, security, governance, and IR. Despite serious polarization in domestic US politics, the notable convergence on China is a clear signal of US intent to pursue the China Threat Theory and try to build a global alliance of liberal democracies against Communism. Recent G7, NATO, and Biden EU Summit also give some signals.

Converge or Clash:

In this state of flux, the inability to move beyond the old hegemonic and conflictual polarity as the only paradigm of great power relations will inevitably lead the world toward the title of the book “Destined for War”. Should this then mean, 21st Century human mind, with unlimited access to information and knowledge, is unable to learn the lessons of history and think of a new paradigm of cooperative and managed competitive plurality for the conduct of IR for the 21st Century and beyond? Must the world keep repeating again and again what it vows “Never Again”?

Is it politics or economics that guides the process of socio-economic transformation internally or determines the course of inter-state relations? The debate is old and intense, but what is obvious is disconnect between these two vital aspects of human enterprise and the paradoxes they have created in the world of our times (Simkhada, 2018). That is the real reason for preventing US-China competition turn into conflict, seeking convergence between Oriental wisdom of Basudhaiba Kutumbhakam or win-win IR with Western caution of Si Vis Pacem Para Bellum. Only with such a transformative IR, we can safely say “No, the world is not Destined for War”.

References:

Allison, G. (2018). Destined for War: Can America and China escape Thucydides’ Trap? New York:

Mariner Books. Fukuyama, F. (1992). The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press. Huntington, S. P. (2016).

The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order.

Gurgaon: Penguin Books. Munroe, R. (2014).

What If? New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Sachs, J. (2008).

Commonwealth Economics for a Crowded Planet. London: Allen Lane. Simkhada, S. R. (2018).

Building Blocks of a New Global Political, Economic, Social, Security-Foreign Policy Architecture. In Simkhada, S. R. (Ed.), Nepal India China Relations in the 21st Century (pp. 36-47), Kathmandu:

Bindu Simkhada. Simkhada, S. R. (2021). Why does Society Repeat Again and Again What it Vows Never Again?

In Simkhada, S. R. (Ed.), Nepal India China Relations in the 21st Century, Kathmandu: SANRAB Publication.

End text.

# Thanks the distinguished author Dr. Shambhu Ram Simkhada and the entire editorial team of the Nepal Council of World Affairs, Annual Journal, 2023:

# Published with the permission of the author: Upadhyaya. N. P.