by Professor Madhukar SJB Rana

South Asian Institute of Management (SAIM)

Background:

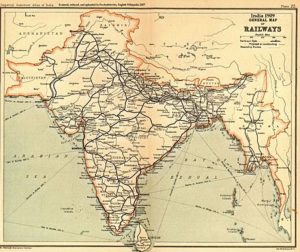

Under British India, it is estimated that, despite absence of industrialization, trade comprised 19% of the sub continent’s GDP in 1948 according to a World Bank study (2007).

This historic level of trade connectivity could be achieved because of factors and forces such as:

- Freedom of movement for trade and traders;

- Freedom of movement for vehicle transport and driver

- The historic 2500 km GT Road connecting Kabul to Chittagong through Delhi

- Freedom of movement for people

- The extensive connectivity offered by the 42 autonomous railway systems (including 32 lines belonging to the princely states) linking all major urban centers, which was the 4th largest in the world

- Indian economy was linked to the British metropolitan cities under Britain-led 19th century globalization which was the factor and force for accelerated trade, investment and sub continental migration.

- In short, “Between 1860-1940, India took part in the globalization process” ( Prof T. Roy 2012) with foreign companies active in organizing foreign trade and commerce located in ports and indigenous companies active in organizing inland trade and commerce

- The flowering of entrepreneurship under British globalization

Post Partition India: From 1947- SARC 1980

As all of South Asia opted for an inward looking development strategy where the ‘commanding heights of the economy’ was left to the state, the share of trade was no more than an unprecedented 2 % of GDP in 1967 (WB:2007).

As all of South Asia opted for an inward looking development strategy where the ‘commanding heights of the economy’ was left to the state, the share of trade was no more than an unprecedented 2 % of GDP in 1967 (WB:2007).

Founding of SAARC 1985 and SAPTA 1995:

In 2002, it reached 4% of GDP at $ 5 billion of which India’s share was 76% or US $ 3.8 billion suggesting that most countries, especially the LDCs, had nothing significant to trade.

Pakistan’s share was 8.0% or US $ 0.4 billion. The remaining 5 countries’ share were a meagre 16.0% or US $ 0.8 billion only. All this dismal showing, despite the completed negotiations on SAPTA with tariff concessions to 5000 commodities, proves that countries were not having surpluses to trade.

Advent of SAFTA 2004:

In 2014 intra-SAARC trade was around 5% of GDP at around $ 30 billion

- As compared to ASEAN’s, in 2014, 609 billion or 25% of GDP.

SAFTA has made no dent whatsoever on SAARC trade:

As even prior to the founding of SAARC in 1980 as SARC it was around 4.0%

- In 1985 it was 3.2%

- In 1990 with liberalization policies it was 2.9%;

- In 2000 under SAPTA it was 4.2%

- In 2005 with SAFTA it was 5.5% and 5.9% in 2010

- And, then down to 5.0% in 2015.

EU got underway with a steel and coal pact between Germany and France. Somehow, we forgot this fundamental fact of shared production for the genesis of the EU.

Instead, built our cooperation on trade when, in 2015 (IMF: World Economic Outlook 2015)

- Bhutan’s trade with SAARC is 0.8%;

- Maldives’ 0.11%;

- Nepal’s 0.81%;

- Afghanistan’s 0.85%;

- Sri Lanka’s 6.78%;

- Pakistan’s 9.73% and

- India’s 78.80%.

It’s clear that tariff reduction does not automatically enhance trade, especially when there are formidable non-tariff barriers (NTBs), ROI, Para Tariffs and Sensitive Lists to trade which serves to show how SAARC nations do not have prominent comparative advantage over others in a few products, suggesting that they are actually competitors with similar products.

It’s now well studied that lack of trade, transport and transit facilitation are the overwhelming obstacles to more dynamic trade.

In recognition of this, SAARC has yet to come up with necessary Protocols and MOUs:

- SAARC Trade Facilitation Agreement;

- SAARC Transport and Transhipment Agreement and

- SAARC Transit Agreement

We may even add other regional agreements in the sphere of logistics management:

- ICT,

- Services and labor migration,

- Regional investment and,

- Arbitration for dispute settlement

Moving from Regionalism to Sub regionalism

SAGQ 1997:

Established in April 1997 as an axiom, as it were, to the ‘Gujaral Doctrine’ 1996. It was founded on the underlying belief that Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal need to create ‘production complementarities’ with which to create surpluses for trade.

Its goals were:

- To create an enabling environment for accelerating economy growth,

- To make overcome infrastructural constraints;

- To make optimal use and develop further complementarities in the sub region and,

- To develop economic and institutional linkages and nodal points for facilitating cooperation on policy framework and project implementation.

SAGQ was to be part and parcel of SAARC by implementing projects through the Action Committee under Article VIII: where all members could participate in a suitable manner for mutual benefit. It was envisioned as necessary, to build the growth quadrangle for integration with the Indian economy with each country who were given responsibility for project formulation and coordination as leader on:

- Sustainable utilization of natural resources (mainly water and energy)– Bangladesh

- Tourism and multiple modal transportation and communication — Nepal

- Sustainable development of the environment —Bhutan and

- Trade and investment—India

SASEC 2002

What started as an integral part of SAGQ in 1997 has now expanded to include Maldives and Sri Lanka under ADB leadership.

(Note: SAGQ was not willing to allow ADB a lead role other than as funder and technical supporter)

Since 2001, it has implemented, as of 2016, 44 ‘regional’ projects for $ 9 billion in sectors such as:

- Energy

- Transport

- Trade facilitation

- ITC and tourism

It is questionable how far the agenda is set by any of the participating countries and how much ownership they have in project formulation, execution, monitoring and evaluation. It should be underscored here that SAGQ had Nepal responsible for overall coordination of the process while projects for the allotted sectors were under the command and coordination of each responsible country for the project formulation and execution. It might be also underscored here that the sources of funds could be from anywhere —not tied to ADB — and all SAARC nations could partake in the project formulation and exception as well as funding.

It is also to be wondered how far the projects are truly sub regional as some are distinctly national or at best bilateral. The real fact of the matter is that it is ADB-led being driven by ADB’s mission to promote sub regionalism and inter sub regionalism across Asia Pacific:

- How far will they serve as ‘honest broker’ is worthy of an explanation?

- Why should they have a monopoly over say World Bank, AIIB, Silk Road Fund and BRICS Bank is another pertinent question.

SASEC has launched its Operational Plan 2016-2025. It has identified 200 projects for the next five years requiring an investment of $ 120 billion. Nepal is to benefit with 37 projects with $ 30 billion investment with 24 billion in 24 energy projects. It is surprising that it is yet project based (and not programmed based) after so joint much policy planning. Why? It claims in its Operational Plan that South Asian sub regionalism will enter a higher phase as SASEC links also with East and South East Asia.

- Does this mean GMEC and OBOR?

- Will it happen when India is slowing down its commitment to IBCIM?

- Does ADB also set its eyes on being banker for BIMSTEC?

SAARC Framework Agreement for Regional Energy Trading 2014:

It envisions cross border exchange and trade in electricity. This agreement allows Nepal to strategize on hydro power exports to India and Bangladesh. Also to receive electricity from neighbors to meet peak demands and shortages arising in different seasons (as for example during winter for Nepal when it imports from India).

Just when energy strategists were at the height of national debate on whether Nepal should export hydro power or use it to transform the national economy— as a major engine of development— by substituting imports of petroleum, diesel, cooking gas, diesel fired generators etc.

In December 2016 comes a shocker from India’s Ministry Power. It totally dampens free trade in letter and spirit. When it requires that imports of hydro energy to India are conditioned on:

- Being generated by GOI state enterprises or

- If in the private sector then it should be an Indian company with at least 51% equity ownership.

Further, this energy trade is also to be ‘harmonized’ with the importing country. It is a real mystery how a LDC will ‘harmonize’ its energy trade with a more developed country and in what areas? As SAFTA flounders on harmonization so this will too— and much more disappointedly because of its technical complexities.

BBIN 2015:

BBIN is another form of sub regionalism that was born after Pakistan rejected the SAARC Motor Vehicle Agreement 2015. Now it faces a further setback as Bhutan Parliament also rejects it as being against its national interest.

We still await what the shape, substance and form of India’s ’Neighborhood First’ regional policy is to look like? Even the visionary announcement of an exclusive SAARC Satellite goes unmentioned it was conspicuous by its absence amongst the 104 satellites so successfully launched by India creating history.

SAARC Current Connectivity Performance:

It may not be an exaggeration to say that SAARC as a movement has cost its tax payers more than the benefits derived from it. It examples a ‘failed model’ of regional integration. It has failed to live up to expectations and it is nowhere near its chosen goals. Commencing on the lowest possible common denominator in 1985, as both India and Pakistan were not supportive of SARC when conceived by Bangladesh, they reluctantly chose to join and create SAARC. Both agreed on the condition that security matters would be out of its agenda. And all decisions would have to be unanimously taken. So far, politics has over ridden all issues and so it languishes on the economic front. The best example is Pakistan refusing to grant MFN status to India even after it ratified SAFTA and both are member of WTO.

SAARC is deliberately made vulnerable to regional politics by keeping the SAARC Secretariat under the tutelage of the foreign ministries. Of course, on paper the institution looks impressive with all its divisions, autonomous centers etc. But it is sheer window dressing since all Secretary Generals and Country Directors are seconded by their respective foreign ministries.

There SAARC Secretariat suffers from weak institutional capacity as diplomats are incapable to function as technical, sector professionals.

The main reason why SAARC is halting is that it does not have a common threat perception. If threat perceptions did play any part in its formation they were:

- Fear of international marginalization of South Asia as a whole resulting from the rapid formation, in

the 1970s, of regional blocs in Europe, Americas, West Asia and South East Asia and - Fear of asymmetry arising from the dominant power of India, as well its strategic positioning as the only country with contiguous borders exclusively with all six members where none others (except Afghanistan) share borders with countries other than India.

Currently, except for India and Bhutan, all SAARC nations welcome China’s OBOR/BRI and think that China’s new global strategy is an opportunity rather than a threat to them. They would even go so far as to call for a SAARC + 1 mechanism within SAARC if not more— to have China as a full member of SAARC.

We are in a veritable ‘SAARC Catch 22’ scenario where, on the one hand, Pakistan wants to keep cooperation on non-core areas and, on the other, India wishes to keep other countries out of SAARC.

As a matter of fact, it may be worthy of mention that when Dr. Tarlok Singh, in 1977, gave birth to the idea of South Asian Cooperation, he had in mind Iran and Myanmar as integral members derived from their civilizational and historical linkages to us.

Even where multifaceted regional security threats loom large in South Asia like mass poverty and inequality; dangerous levels of youth unemployment and underemployment; food, energy, water security issues, as well as challenges arising from the need to manage multiple natural disasters arising simultaneously, South Asian leaders are in no hurry to cooperate and to begin to recognize them as a common security threat — albeit of the nontraditional kind— deserving integrated use of its common natural resources and investment in regional public goods for their exploitation.

The continued instability in domestic politics of South Asian nations is another factor retarding dynamic regional and sub-regional collaboration. There is a tendency in the smaller nations to put all the blame on the hegemonic neighbor, India: and thus seek to look outwards for support rather than recognizing one’s own leadership failures.

On the economic front, trade with outsiders (USA, EU) as competitor is a fact of life amidst South Asian nations. The export basket is similar– readymade garments; leather; agri products, cotton etc and no one country has a dominant comparative advantage. Similarly, all engaged in import substitution vigorously from 1947-1990 with no country developing a unique industrial niche to be able to set up production and supply chains within the region.

However, it must be tampered with recognition of the sad fact that India, as a natural leader, chose to rest on its hegemonic advantage arising from its geography and its economic (80% of SA GDP) and demographic (70%) size. It could and should have done more towards integrating its neighborhood.

Perhaps, its leadership then lacked the vision of India as a global power until they witnessed the remarkable rise of China as a regional economic power in the 1990s and now as a world power second only to the USA.

The GEP Report called for a doable and pragmatic Social Charter for a sustained, focused and methodical cooperation in areas of regional social development— poverty eradication, human rights, gender equality, child rights, human development etc. This is admirable. Similarly, it called for a a graded process of regional economic cooperation from the formation of SAFTA in 2010 to Custom Union in 2015 and Economic Union in 2020.

It based its recommendations from the successes of the European Union model of regionalism that was well replicated by ASEAN. Here it blundered in selecting a model alien to our history and contentious political and social realities in the absence of a common threat.

In fact, devoid of proactive leadership from India, its hegemonic behavior is, ironically, felt as a threat by most nations.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Neighourhood First Policy’ remains an unknown rhetoric while he seeks a ‘Modi Doctrine’, as it were, in foreign policy that wills India to be a leading power in a multi polar world assuming leadership, especially in Asia Pacific, rather than taking the balancing role of the past (Trellis:2016). However, it must be underscored here that this will no be possible (contrary to Trellis’ view that aligning with the US would suffice— unless it can successfully lead SAARC as the supreme regional leader by demonstrating transformational leadership on three fronts simultaneously — political at the G2G level; economic at the B2B levels and social at the P2P level.

The worsening Indo Pakistan relations clearly shows that the limits to SAARC as an institution of regional cooperation for peace, stability and development has been exhausted.

It has reached its breaking point. Therefore, ‘Out of Box’ thinking is a strategic necessity on all fronts — political, social and economic. At least 70%-75% of the responsibility for the future of SAARC lies with India because 70% of territory and 77% of the GDP and population of South Asia is in India.

Foreground:

All SAARC nations seek high, sustained growth for long periods to be able to eradicate poverty and hunger and mass illiteracy, disease and underemployment. All seek 7.5-8.0% GDP growth while setting sights at 10.0% to speed up the transformation to a middle income country by 2030.

setting sights at 10.0% to speed up the transformation to a middle income country by 2030.

Should not the SAARC Think Tanks collectively think out of the box on how we, in the region, can be the fulcrum of the global economy before 2050 by surpassing both China and USA? I say this, because confidence building endeavors whether through Track I, II and now IV will not yield much harping on our glorious civilization without laying down a bold, imaginative regional vision for collective change towards globalism and our place in planet earth of the 21st century.

Such a collective vision may bridge the trust deficit and generate the political will in the interest of the region and each nation, especially given the demographic dividend and the estimated 12 million jobs to be created annually for regional political stability, peace and harmony.

To begin with, this collective vision needs to go beyond the hackneyed ‘trade complementarity’ and ‘transport connectivity’ towards a much broader meaning of connectivity to stress ‘integration’ not simply ‘cooperation’ through ‘production complementarity’. They should extend to ‘economic connectivity’, ‘financial connectivity’, ‘institutional connectivity’, ‘legal connectivity’ and, not least ‘policy and local planning connectivity’.

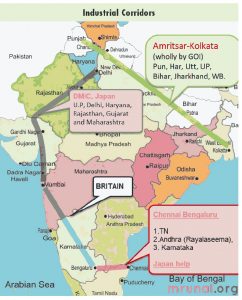

We have to move beyond the theory of comparative advantage and competitive advantage to creating sub region and regional growth hubs and growth corridors — urban hubs and spokes, if you like— through creation of supply chains and undertaking value adding regional and sub-regional investments through backward and forward linkages. We need foremost, to create manufacturing production and logistics networks or economic corridors (ADB: 2014).

In short, we need to place at the center of South Asian regional connectivity its geography. That must include harnessing the ‘new frontiers of our collective resources’, namely the Himalayan rivers and the Indian Ocean. (This was the original vision with which Dr. Tarlok Singh set out on his academic mission in 1977 with his counterparts in Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka when he created the CSCD programme of studies).

It is worthy of a revisit by all think Tanks.

Now that Afghanistan is a member of SAARC, we must start to conceive South Asia – what I have been underscoring since 2000— as comprising ‘4 economies in 1’.

They are:

- The eastern seaboard as the hub encompassing the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghana Rivers flowing from the Himalayas into the Bay of Bengal economically linked with Myanmar-Thailand-Indo China;

- The southern seaboard could roughly be conceived as the hub around the axes Vizakapatanam-Sri Lanka-South East Asia-Australasia. (Note: they comprise BIMST-EC nations)

- The western seaboard comprising the hub around the axes Maldives-Mumbai-Karachi-Persian Gulf-West Asia and finally,

- The grand landmass of the Hindu Khush-Karakoram-Himalayas extending from say Uttarakhand – Uttar Pradesh-Himachal Pradesh-Delhi- Islamabad-Kashmir-Kabul-Central Asia (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan,Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan).

Whatever the fate of NAFTA, TPP and EU after Brexit, Tumpism and the wave nationalist populism sweeping the West, I firmly believe that regional blocs will continue to be the building blocks of the new world order of the 21st century multi polar world— particularly following the decline of the UN order dominated by the West with its neoliberal international order.

One should stress here that SAGQ/SASEC/BBIN and BIMST-EC fit in well with India’s strategic ‘Look East’ policy. However, China’s ‘Look Westward’ strategy seeking to lead to balanced regional development within its own territory, and now elaborated in the OBOR/BRI strategy, will without doubt, pull the entire SA eastern seaboard northwards towards growth axes like Tibet; Yunnan and even Sichuan.

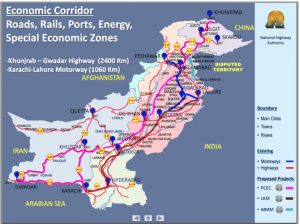

The BCIM corridor will further accelerate this momentum. The other Chinese strategy, namely to create Trans Himalayan Economic Corridors (THEC)– now exemplified by China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) linking the Gwadar Port in Baluchistan with Xinjiang Province will further speed up this geo economic motion. The same will happen when Nepal implements the OBOR/BRI projects with the Chines pledging $ 8.5 billion out of the $ 13.5 billion in the just concluded Nepal Investment Summit 2017. It is rumored that this could be as high as $ 13 billion for the rail links envisaged up to Kathmandu from Lhasa and, further, to Pokhara and Lumbini from Kathmandu.

With these developments in the horizon, I anticipate that a new sub region, namely the Trans Himalayan Sub Region, could—and should — emerge with the completion of the Mid Hill East West Highway of Nepal and its planned 10 urban centers that will link Nepal to Utarakhand in the West and Sikkim in the East.

Hopefully, it will be extended to Himachal Pradesh, Darjeeling, Kalimpong and Bhutan to create the world’s first Sustainable Green Himalayan Economy to combat global warming and climate change ; as well as creating the much missing highland lowland links in the sub continent’s economy through harnessing of the Himalayan waters and creation of multi sector River Basin Plans.

When South Asian leaders are fully confronted by the multifaceted regional security threats arising from pervasive poverty and inequality; unemployment and migration; energy and water scarcities, and the challenges arising from the need to confront terrorism and manage multiple natural disasters occurring simultaneously, then cooperation in the sharing of one another’s natural resources will become paramount for the peoples of South Asia. Such future security threats might override the lack of a common security perspective as we are yet trapped by the legacies of our colonial history of partition and animosity.

As India is starting to perceive the American presence in the sub-continent is not against its national security interest, and the US diplomacy influences the smaller regional powers from alliances with other global powers, India may start thinking beyond the politics of regional hegemony and be encouraged to come forth with a more enlightened ‘neighborhood first’ policy. The success of both EU and ASEAN is, I submit, precisely because Germany and Indonesia put neighborhood first rather than Germany or Indonesia first. Regionalism succeeds when the Big Brother not only leads — but leads from behind and not the front.

It was assumed that SAARC could progress by freezing contentious political and territorial issues and set in motion confidence measures. No Indo-Pakistan entente cordiale has appeared in the SAARC atmosphere. In fact, matters have worsened to such an extent that the November 2016 Summit to be held in Islamabad was cancelled. Along with the refusal by India to confirm the appointment of the Pakistani nominee as Secretary General until February 2017.

For both India and Pakistan the Kashmir question continues to become a highly charged issue for national survival. With Pakistan claiming that it is the raison d’être for its integrity as a nation state; while India counter charges that it is at the core of its very existence of as a secular state.

India rightly incorporated People to People diplomacy (P2P) as a core component of SAARC. That being said, it refused to let go of the tight grip on SAARC affairs by the foreign affairs ministries. There was little or no space for NGOs to access Summits and the Secretary General. Track II dialogues were sadly mere extensions of the foreign ministries filled with retired government and security officials and state dependent think tanks.

To truly generate a Social Union of South Asian Nations, we need to give full freedom to the Bengalis, Kashmiris, Punjabis, Sindhis and Tamils to communicate and dialogue with each other massively across the borders at all levels of society to fully rediscover and reconcile with each other based on cultural and linguistic affinities while permitting trans-border passage to meet with their divided families. It would be ideal if such passage of rediscovery and reconciliation could have been facilitated by the vast South Asian diaspora in America, UK, Australia and Europe.

We should start thinking of involving them in the SAARC process too. To inculcate religious harmony in SAARC, a biannual Social Summit representing all the prominent religious leaders of each of the major religions should find space in SAARC to break the barrier of religious disharmony and conflict caused by short sighted politicking for vote banking to come to power. These leaders would be entrusted to dialogue to reach out to the peoples of South Asia by defining the core values derived from all our religions. They should be adopted as the core values of SAARC.

Similarly, the SAARC Secretariat should hold other Social Summits such as Council of Eminent Women; Council of Dalits; Council of Tribals etc. to awaken and uplift the marginalized and discriminated communities in our societies with empowered and emancipated for social justice, equality and equity for all.

These P2P Social Summits could recommend to the government the action plan and programmes that need to be designed by the SAARC Secretariat to put into implementation the noble goals laid down in the SAARC Social Charter.

It must be firmly reiterated here that the SAARC Social Charter is a hallmark achievement of the role that civil societies in South Asia play in our body politic. It demonstrates how much more powerful, prominent and innovative the role of civil society in SAARC is as compared to ASEAN, for example. But the SAARC Social Charter should not duplicate agendas already in active discussion in the various UN agencies. It must come forth with SAARC specific action plans with clear cut targets for which the G2G action must be pressured to back with the right fiscal policy support with the required funds for regional programmes. A common minimum regional social programme will go a very long way to make SAARC and P2P a living reality where the poorest of the poor in SAARC communities can begin to think regional while acting national. So much for P2P.

Now, let us tackle the role and function of business to business (B2B) connectivity by activating the various national business federations to think regional— not simply national and extra national. So far, the SAARC Chamber of Commerce and Industries, located in Islamabad, has been doing a commendable job of seeking to B2B connectivity. It may be mentioned here that this SAARC CCI is the only autonomous regional organization which, legally, even the SAARC is not: sadly, it is still an inter-governmental organization rather than an autonomous association.

It is high time that we called upon the private sector to play an active role in SAARC. Thus we should call for the SAARC Economic Agenda to be fully formulated by the private sector in a B2B format — just as the SAARC Social Charter was an illustrious result of NGO leadership as a P2P initiative.

We underscore here that regional integration is most successful when it is premised on the principles of the regional division of labor garnered by principles like free trade, free labor movement, free competition, free convertibility, economies of scale, economies of scope, supply chains and banking and finical access. Under SAFTA we see how NTBs, PTs, SLs, ROIs severely curtail all the desired regional division of labor so that local and national labor, farm, business and banking interests are protected. Due to the absence of a regional grand vision from the business leaders protectionism— quite understandably—comes to the fore.

It is suggested here that Indian business conglomerates listed in the Forbes billionaire list of whom there are 50-60 people get together to catalyse the process of formulating the SAARC Economic Charter so that they begin to see themselves as South Asians and create SA-MNCs with win win partnerships with the other national business houses and federations.

I call for India business conglomerates to lead regional integration with a Pan South Asia vision because;

- 77-80% of the GDP rests in India;

- Structuring South Asian division of labor on a North South division of labor is unstable for Planet Earth and provides no relief to our agriculture dependent labor force where 66-70% are employed;

- WTO progress has been retarded for years with its inability to arrive at multilateral agreements over agriculture and rural development by restarting the Doha Round negotiations;

- The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 has demonstrated clearly on the objectivity and independence of the IMF as a world financial institution and, last but by no means least,

- Export led growth based on interdependence with the North will not suffice to create the 12 million jobs need to have full employment in South Asia — nor to jump start high growth at say 8-10% per annum of next 12-15 years to become an industrial society.

The North has entered into a state of structural stagnation around 1.5 -2.0 growth facing a greying economy. How may they begin to strategize on the grand vision?

This can be done on two fronts:

- SAFTA and

- SAFTA— it has all the needed provisions, as per the agreement– such as principles, concepts and desired measures including the establishment of venture capital funds to promote cross border trade an investments.

On the SAFTA front push for speedy negotiations over trade facilitation and agreements on the various logistics treaties and agreements already mentioned. Such treaties could also involve ratification to existing international treaties on transit, rail/river transport, clearing and forwarding and insurance etc. Where 20-30% of CIF values comprise logistics costs the gains to trade, export competitive and consumer welfare will be significant.

Similarly, huge investments in regional laboratories will facilitate harmonization of health and safety standards, including harmonization and standardization of trade, commerce and banking documentation and maximum use of electronic data systems for customs clearance and surveillance and monitoring.

Re SAFTA it is to be underscored that SAARC has not renounced this agreement and so it is still legally valid. I call on the Forbes billionaires of South Asia to revisit it and seize opportunities arising from it. To begin with SAFTA excludes the primary sector with high tariffs and heavy protectionism while SAPTA could permit regionalization of our primarily sector for a win-win solution. How?

Let us negotiate commodity arrangements around selected products with potential comparative advantage globally and regionally in each SAARC country and scale it up by avoiding intra and inter regional competition to create supply chains, economics scope and scale and re negotiate our tariffs, NTBs and ROIs suitably, including fine tuning the monetary, credit, foreign exchange and fiscal policies towards the success of this grand regional venture. We may envisage SWAP agreements to encourage barter like trade in our own national currencies which will boost the local bond market. Which may be the probable candidates for the creation of a multi sector SAPTA Regional Integrated Commodity & Services Agreement (SAPTA-RICSA)?

- Agriculture: fruits, vegetables, organic farming, jute; fisheries; tea, coffee, tobacco, fats and oils, rubber, cotton and cardamom; ginger; milk products;

- Forestry: medicinal herbs, timber, bamboo;

- Mining and Minerals: iron ore, iron and steel products, petroleum products, organic chemicals, fees, coal, uranium

- Manufacturing: yarn, textiles, leather and leather products, household equipment, furniture, pharmaceuticals, alternative medicines, transport vehicles, electronic products, telecommunication, machineries, gems and jewellery, woolen products, food processing;

- Services: B2B cooperation to promote social entrepreneurship and develop cultural products of relevance to local communities in local ecologies by creating venture capita funding (VCF), market development assistance (MDA), branding, patenting an merchandising through R&D support and application of the 4P approach to local development by supporting local human capital, social capital and intellectual capital, integrated supply chain management (ISCM), creation of SEZs, EPZs, EPVs, Industrial Districts, World Class Institutes for Technical and Vocational Skills required by the conglomerates with appropriate fiscal incentives.

Partnership with NGOs and CBOs need to be underscored. The establishment of a Construction SA MNC will help to create a vibrant world class construction industry where we can bring back those from the Remittance Economy to meet our own construction needs or to obtain better deals for our South Asian manpower in West Asia.

Trade and investment in goods and services are vitally necessary for effective regional cooperation. Investment by subcontracting and joint venturing must be expanded to investments by accessing each other’s stock, bond and money markets through maintaining foreign exchange and capital convertibility. This too may not be ideal in order to embrace globalization effectively. More than mergers and acquisitions of firms, corporate leaders should be committed to form transnational corporations with a South Asian identity rather than a national identity and allegiance. Intra-firm disputes arising could be settled on the basis of a regional dispute settlement treaty.

It may be recalled here that as far back as 1984 Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister Hameed had proposed that we should think of creating regional joint ventures for various commodities to access each other’s and global markets. Independent corporations subscribed to by all governments was proposed as the modality. Now, perhaps, the private sectors is sufficiently mature to develop these MNCs themselves.

I submit, it is more vital than the resources deficiency required to create connectivities. Yes, we have the South Asian Development Fund with $ 100 million, which can fund regional projects to pursue aims and objects as in the Social Charter. Perhaps, we also need an Investment Fund which will be contributed by governments and private sectors of the region, including international financial institutions and our foreign settled diaspora to fund regional projects. These projects should be open to buying of shares and bonds by the peoples too. It is estimated that investments required in infrastructure in South Asia are in excess of $ 110 billion to sustain 7-8% regional GDP growth.This is a whopping slice of regional GDP which calls for such an Investment Fund.

Regional Security:

Regional security must enter the agenda of SAARC Summits. It can’t be wished away or kept under the carpet. They are the greatest impediment to South Asia connectivity. In the face of dominant hegemony, it is natural for smaller powers to seek extra regional power support for their own security and promotion of national interest.

The gravest threats to South Asia are Maoism, terrorism, the entry of evangelical Christianity and the politics of vote banking and divide and rule in the wake of pervasive corruption. And all this, in the background of a world faced with low growth, unprecedented inequality, anarchy and instability given debt and financial bubbles and growing military industrial complexities. Where nationalism is regressing to ‘revolutionary nationalism’.

While approach to connectivity may unleash favorable geo politics and geo-economics for South Asia. Yet it is our geo psychology of fear and suspicion of each other that we must grapple with both freely and frankly in a security dialogue.

Mismatch between fears and perceptions are a commonplace which must be clarified. India fears ganging up by all against it, while others fear hegemonic domination. Long standing border disputes remain unsettled. Smaller nations fear larger ones monopolizing the benefits from cooperation. If we take the UN definition of terrorism to mean all forms of violence targeting civilians for political ends, we might share intelligence and cooperate to develop counter insurgency measures as well as offer common tactical training to our intelligence agencies.

Cooperation in cyber intelligence should provide immense opportunities for confidence building as it impacts both governments and well as the private sector. So to in disaster management and UN Peacekeeping Operations where we should be having a greater presence.

Empower the SAARC Secretariat:

Empower the SAARC Secretariat:

Last, but not least, thinking out of the box requires that the SAARC Secretariat should be led by an eminent regional statesman chosen collectively by the Summit for a period of 6 years. He should hold the rank of a Minister who could deal directly with Heads of States/Governments.

One of the areas in which the Secretariat should play a specialist, dynamic role is in designing common strategies for SAARC is to be able to influence policies and procedures, as a regional bloc, at the WTO, IMF, World Bank, Asian Development Bank and United Nations and its specialized agencies. Ironically, at present it is being used by UN specialized agencies to project regionally its organizational interests duplicating commitments made nationally.

Another way by which it could be empowered is by requiring all UN specialized agencies to use the Secretariat as the common focal point for planning and programming its own regional programmes for South Asia jointly with SAARC Secretariat. And to allow the Secretariat to implement these programmes with required technical specialists seconded to the SAARC Secretariat by each UN regional organization. For example, regional organizations of UNICEF, UNDP, UNFPA, WHO etc. located in South Asia should use the SAARC Secretariat as the executing agency — not individual ministries in individual governments. This innovation will also drastically cut back the budgetary costs of these regional outfits which will prove to be salutary as the UN is expected to face severe financial crises.

All decisions of the Technical Committees, as well as other Committees, should be based on the principle of majority and not consensus. The rule of unanimity may be continued at the level of the Council of Ministers and Summit.

This model of integration through B2B must be guided by principles such as caring and sharing; respect for environment and stakeholders; equity and equity and speedy settlement of disputes through arbitration. B2B also calls for changes in G2G behavior through partnership with B2B in policy and planning deliberations to grow the region’s economy.

What is remarkable is that SAARC has survived near-war scenarios, proxy war scenarios and acute extra territorial intelligence operations to destabilize nations. Many times the Summits have been vetoed by India many times over as in the case of Sri Lanka’s LTTE problem; Pakistan terrorist attacks; Royal take over in Nepal and rise of fundamentalism in Bangladesh. But it restarts. Why? Because politicians, bureaucrats and security organizations know full well that the common men and civil societies are solidly behind it.

Increasing more the private sector too.

What keeps SAARC chugging along? There are seven generic fears:

- Fear of geo strategic marginalization by the rapid emergence of regional blocs in North America,

Europe, South East Asia, Latin America, Africa and West, Central and South East Asia; regional blocs being the core foundations of globalization; - Fear of domination by the Industrial North as result of the demise of the Soviet Union;

- Fear of the historic progress made by China through market oriented reforms; fear of the consequences of internal conflicts on regional peace emanating from lack of human security in South Asia;

- Fear of domination by India owing to its asymmetric power and

- The continued dynamism within ASEAN and Central Asian Republics a regional organization will embolden SAARC to survive and

- Fear of dependence on any Super Power.

There is also one grand hope that keeps South Asians together:

- The SAARC process allows India and Pakistan garner mutual trust and confidence by speaking to each other which, hopefully, will lead towards eventual bilateral detente and rapprochement and thereby keep the prospects for South Asia to be, eventually, the other Global Power of the 21st century.

- If the 21st Century is to be the Asian Century, then, China and India must reconcile their strategic differences. One such platform where they may be able to do so is in SAARC. If they fail to do so, a New Cold War reins in on us Much deadly than the last as we are now in the realm of Hybrid War which will be applied in competition for the finite natural resources in the world, including competing intensely in the Oceans, Himalayan region, Outer Space and Cyber Space with massive buildup of their military might that is bound to be detrimental to the Asian Renaissance after 300 years of colonization and imperialism.

REFERENCES:

- World Bank (2007); South Asia: Grwoth and Regional Integration Report, Washington, DC

- Tirthankar Roy (2012); Trading Firms in Colonial India, Harvard Buisness School, www.hbs.edu/businesshistory/Documents/roy-trading-firms-colonial-india.pdf

- Priyanka Kher (2012); UNCTAD, Geneva unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ecidc2013misc1_bp5.pdf

- Madhukar SJB Rana (1998); The SAARC Growth Quadrangle; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kathmandu

- Madhukar SJB Rana (2000); The Future of SAARC; Institute of Development Studies, Kathmandu

- Madhukar SJB Rana (2003); From SARC To SAARC and Which Way Forward?, South Asian Policy Research Institute, Colombo

- Madhukar SJB Rana (2002); Future of SAARC; Institute of Development Studies and Institute if Foreign Affairs, Kathmandu

- Ashley J Tellis (2016); India as Leading Power; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace http://carnegieendowment.org/2016/04/05/india-as-leadingpower/

- Prabir De and Kavita Iyengar Editors (2014); Asian Development Bank

- Parthapratim Pal (2016); India BBIN Trade Opportunities and Challenges; ORF and Asia Foundation, New Delhi http://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ORF-Issue-Brief_135.pdf