Ace Collymore

Foreign Policy Analyst & Journalist

Canada

For the past 15 years, India and China have vied for favorable diplomatic and trade relations with Sri Lanka thanks to its strategic location in the Indian Ocean.

While popular perception indicated China had outpaced India, the recent economic and political turmoil in Sri Lanka seems to have given India’s foreign policy a fresh lease of life in the island nation.

Sri Lanka is in the middle of its worst economic crisis since independence from Britain in 1948. The country has been rocked by protests as people seethe with anger over soaring prices and shortages of food and fuel.

Last week, Mahinda Rajapaksa resigned as prime minister after his supporters clashed with peaceful protesters, sparking a deadly night of violence on 9 May.

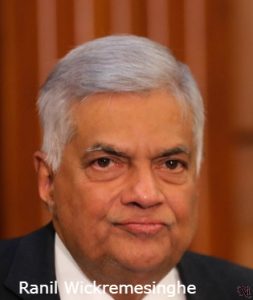

Ranil Wickremesinghe, who took over as PM, said the country’s economic problems would get worse before getting better.

He appealed for outside financial help, including from India.

India has never been a major lender to Sri Lanka, unlike China which by the end of 2019 owned a little over 10% of Sri Lanka’s outstanding foreign debt stock.

In early 2021, with the economic crisis looming, the Sri Lankan government had also obtained a 10 bn yuan ($148m; £119m) currency swap facility from China to tackle its foreign exchange shortage.

But now, India is slowly emerging as one of the biggest providers of aid to Sri Lanka.

Colombo has racked up $51bn (£39bn) in foreign debt. This year, it will be required to pay $7bn (£5.4bn) to service these debts, with similar amounts for years to come.

The country is also seeking emergency loans of $3bn to pay for essential imports such as fuel.

While the World Bank has agreed to lend it $600m, India has committed $1.9bn and may lend an additional $1.5bn for imports.

Delhi has also sent 65,000 tones of fertilizer and 400,000 tones of fuel, with more fuel shipments expected later in May. It has committed to sending more medical supplies too.

In return, India has clinched an agreement which allows the Indian Oil Corporation access to the British-built Trincomalee oil tank farm.

India also aims to develop a 100 MW power plant near Trincomalee.

Many in Sri Lanka feel that India’s growing presence in Colombo could mean a “dilution of sovereignty”.

“For the past year and a half, there has been a crisis in Sri Lanka and we believe India has used this to serve its own interests. Yes, they gave some credit, some medicines and food but [they are] not being a friend. There is a hidden political agenda,” said Pabuda Jayagoda of the Frontline Socialist Party.

But others are more accepting of Indian help.

“Let’s not blame India for our woes,” says V Ratnasingham, an onion importer in Colombo. “We are still getting onions from India at a decent price and they are giving us credit in times of crisis. It’s the Sri Lankan government’s failure that onion prices have trebled.”

The suspicion over India’s intentions right now comes against the backdrop of Sri Lanka’s ties to China.

After Mahinda Rajapaksa took charge as president in 2005, Sri Lanka’s drift towards China was believed to be a preference for a “more reliable partner enabling domestic economic development”.

More and more infrastructure projects – including the multi-billion dollar Hambantota port and the Colombo-Galle expressway – were awarded to China.

Chinese President Xi Jinping‘s maiden visit to Colombo in 2014 was also a clear diplomatic signal to Delhi.