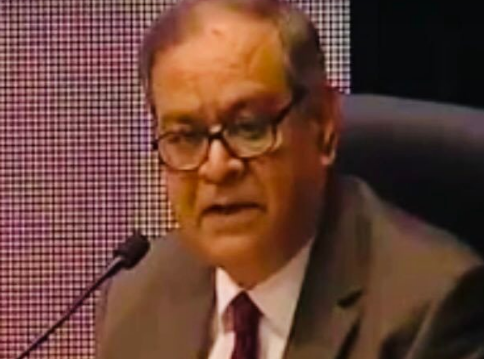

Ambassdor ( late) Sohail Amin, Pakistan

–Pakistan important for trade and commerce between South and Central Asia, East and West Asia-

The Asia Pacific/Indo Pacific region is at the world’s focus for its growing political importance, its fast economic development, and its strategic position on the sea lines of communication (SLOCs).

It has 60 percent of the world population, a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of more than $40 trillion and hubs of economic power that now compete with the West.

It has four sub-regions spanning the Asian continent bordering the Indian and Pacific oceans: Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania and South Asia.

Its seas command the vital and busy pathways of maritime activity. Three of the most important Straits-Malacca, Sunda and Lombok-situated here permit shipping of trade and energy vital to the East and West.

China’s rise as a major power has added a new dimension to the region’s geostrategic importance.

A regional security order which is a complex combination of actors and policies is no longer associated exclusively with political and economic interdependence.

The Asia Pacific region has undergone fundamental changes in its regional organization, security order, and power structure in the post-Cold War era.

The region has become a powerhouse of global economic and geopolitical transformation as part of Asian ascendance in comparison to the West which in general perception is no longer the world’s center of gravity.

The accretion of military power that has inevitably followed the region’s economic growth is altering the balance of power within the region and between Asia and the West.

According to the Western analysts, the key strategic issue today in East Asia is the rise of Chinese power.

For nearly three decades, the Chinese economy has been growing by 7 to 10 per cent annually. China’s defense expenditure has risen by an even larger percentage. Chinese leaders assert China’s ‘peaceful development’, but Western analysts long accustomed to power politics of the West have their doubts.

They think China will exert its weight towards seeking hegemony in East Asia which might lead to conflict with the United States and Japan.

Another factor which has tilted the balance of power is Japan’s economic slowdown and relative decline in its influence in the region.

To hedge against a possible security gap, Japan, South Korea, India, Vietnam, Australia and others are boosting intra-regional and bilateral trade, defence and diplomatic ties, selling military equipment to each other, and conducting joint military exercises, sponsored by the U.S. which views China’s rapid growth with apprehension.

This does not mean that the U.S. is playing a backseat role in this strategy. Its decision to re balance its forces so as to deploy 60 per cent of its combat ships in the Asia Pacific region by 2020 did not come as a surprise.

It has built a web of Strong alliances around China’s periphery by developing cooperation with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia and India.

This proactive involvement of the U.S. in the region, and its unabashed propping up of its declared strategic partners in South Asia as a kind of ‘counter weight’ to China, only translates into what is generally and not so wrongly understood as its China containment policy. This has raised concerns in South Asia.

On its part, China is now attracting regional states with its economic power and is offering a competing vision of shared destinies in economic progress as a soft power to the U.S.-centric ‘hub and spoke’ system of alliances that was established in the post-World War II period.

China’s alternative has been constructed around trade relationships and diplomatic initiatives manifest at the East Asia Summit, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)+3 forums, various Chinese bilateral free trade initiatives, and China’s ‘charm’ offensive.

As a result, a new web of power relations is emerging in Asia today inspired by China’s rise and the perceived relative decline of the U.S. The countries of the region are bolstering mutual ties eclipsing the U.S.-led model of alliances by a broader, more complicated and more diffused, web of relationships in which Asian countries are the primary drivers.

This developing web has provided an impetus to the new US grand strategy in the region by leveraging relationships among like-minded countries to share its burden of managing China’s rise and preserving a balance of power.

Yet its current dynamics of the US-China-Japan triangle will continue to haunt the region and may even confront the present cozy ASEAN-driven model of security with new challenges.

Closer to more real fault lines than the specter of rising China is the South China sea issue that will remain a bone of contention between China and the claimants-Brunei, Malaysia, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Vietnam, on the one hand, and between the US and China on the other.

Lately, Vietnam and the Philippines have also asserted their claims.

ASEAN states are divided over the role of extra-regional powers in the South China sea.

Some regional countries are leaning on the US to get more deeply involved, but China is averse to any outside interference and wants to resolve the issue bilaterally.

The Asia-Pacific region’s diversity requires a security order of its own. China’s new concept of security encourages economic inter-dependence and stresses finding solutions of nontraditional security challenges like terrorism, environmental degradation, disaster management, water management, drug trafficking and health related issues.

Rising due to its capacity and stakes in the region will continue to be the key in such an order.

This might strain the existing structure of regional important question is how the region would address the competing interests of China and the US?

With the current emphasis on economics as the driving force in international relations, regional flash points such as territorial disputes in the South and East China Sea, Kashmir, Tibet and the North Korean nuclear issue tend to get overshadowed. But that does not lessen the danger they pose to regional security as they continue to cause tension and mar growth of bilateral relations.

For South Asia, the strategic shift from Eurasia to Asia Pacific has become an urgent concern in the wake of US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Geo-strategically, Pakistan is important for trade and commerce between South and Central Asia, East and West Asia.

In its efforts to bring peace in Afghanistan, Pakistan has been contributing significantly to establishing new security model in the region. (The US forces have already left Afghanistan: Ed).

Russia, China, Iran and Pakistan constitute a relevant regional powerbase in this respect.

Pakistan can give practical shape to its proposal of providing connectivity’ to ASEAN via western China and Central Asian Republics by both land and sea through the Gwadar Port and the prospective China-Pakistan Economic Corridor which is introducing a new and positive dimension to the emerging Asia Pacific scenario.

Article written jointly by Ambassador (retd.) Sohail Amin, Muhammad Munir and Muhammad Nawaz Khan.